Wage Growth: Why the Fed Still Has a Problem, Even as Inflation Cools

The July 2025 CPI report confirmed what markets had been hoping for: U.S. annual inflation slowed to +2.7% year-on-year, still above the Federal Reserve’s 2% target but comfortably below recent peaks. However, beneath that headline lies a more stubborn challenge for policymakers — wage growth.

At +3.9% y/y, wages are still rising faster than prices, meaning real purchasing power for workers continues to expand. While that’s welcome news for households, it complicates the Fed’s mission to tame inflation sustainably. As Chair Jerome Powell has said repeatedly, the sweet spot for wage growth consistent with 2% inflation is 3.0–3.5%.

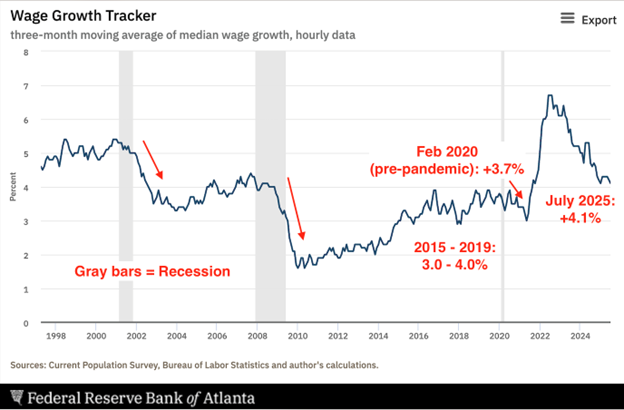

The latest Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker update for July 2025 tells us a lot about why wages aren’t normalizing quickly — and why the Fed may not be ready to declare victory just yet.

1. The Long-Run Perspective: Wages Still Running Hot

The three-month moving average of median hourly wage growth cooled to 4.1% in July, down from 4.3% earlier this spring and well off the record 6.7% peak of August 2022.

- Pre-pandemic, in February 2020, wage growth stood at 3.7%.

- From 2015 to 2019, it typically ranged between 3.0% and 4.0%.

- Historical patterns show wage growth rarely falls significantly without a recession.

Why it matters: The current wage growth rate remains well above Powell’s comfort zone, and economic growth is still decent — the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow estimate for Q3 stands at +2.5%. Without the economic slack caused by a downturn, wage pressures tend to decline only gradually.

Key takeaway: Without a recession, history suggests normalization will be slow. This helps explain why the Fed is cautious about aggressive rate cuts despite cooling CPI.

2. The Switchers vs. Stayers Signal: A Recession-Style Drop Without a Recession

The 12-month moving average data shows something striking:

- In late 2022/early 2023, job switchers earned 2.2 percentage points more in annual wage growth than job stayers — the largest gap on record.

- By July 2025, that gap has collapsed to 0.0 points — the same pay growth for both groups.

Historically, such a rapid compression in wage differentials has only occurred during or just after recessions:

- 2001 recession: gap bottomed at -0.1 points in January 2004.

- Great Recession: gap hit -0.7 points in January 2010, seven months after the downturn ended.

Why it matters:

- The loss of the “switching premium” signals weaker marginal demand for labor — companies no longer feel compelled to pay extra to lure workers away from their current jobs.

- For corporate America, this is a cost-positive trend. For the labor market, it raises questions about momentum.

Key takeaway: Labor demand has cooled from its post-pandemic extremes, but aggregate wage growth remains high. This “stall speed” dynamic reduces near-term layoff risk, but also suggests wage disinflation is losing momentum.

3. Sector-Level Pressures: The Majority Still Above Average

Some industries are still pushing aggregate wage growth higher:

- Public Administration: +5.8%

- Leisure & Hospitality: +4.6%

- Education & Health: +4.5%

- Construction & Mining: +5.0%

- Finance & Business Services: +4.5%

Together, these five sectors represent ~69% of total U.S. nonfarm employment, and all exceed the July overall wage growth rate of 4.3% (a 12-month average).

- Only Manufacturing (+4.0%) and Trade/Transportation (+3.6%) are pulling the average down.

Why it matters: Sector concentration means wage stickiness in a few large industries can keep the national number elevated for longer — a challenge for inflation control.

The Fed’s Policy Dilemma

The combination of still-strong wage growth, no recession, and above-target real wage gains puts the Fed in a bind:

- Cutting rates aggressively risks reigniting inflationary momentum, especially in services-heavy sectors.

- Keeping rates higher for longer risks slowing growth more than intended.

Markets are pricing in 50% odds of three rate cuts this year. But if the Fed is data-dependent, the stickiness in wage growth could force fewer or later cuts.

Bottom Line

The July wage data underscores the Fed’s core challenge:

- CPI is trending lower, but wage growth — especially in key industries — is still too hot to align with the inflation target.

- Labor market momentum has cooled, but not enough to generate the slack that would bring wages down faster.

For now, Powell’s problem is that the inflation fight isn’t over. The question isn’t whether wages will slow — they likely will — but whether they will slow fast enough without a recession. That’s the balancing act shaping U.S. monetary policy for the rest of 2025.